Back in the scariest month of the decade, March 2020, I went to London for the day with some fellow photographers. The plan was to attend The Photographer’s Gallery in the morning, to see the finalists of the 2019 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation prize. In the afternoon we were due to visit the Photography Centre at the Victoria & Albert Museum, followed by lunch and a photowalk around Kensington and Chelsea, before returning home. It was a chilly day with grey, flat light and on-again, off-again drizzle. The thought of walking around in the rain became less and less appealing. I wanted to sit down somewhere warm with a coffee and pastries instead. I hadn’t done any research before attending The Photographer’s Gallery, so I had no idea what I was about to see.

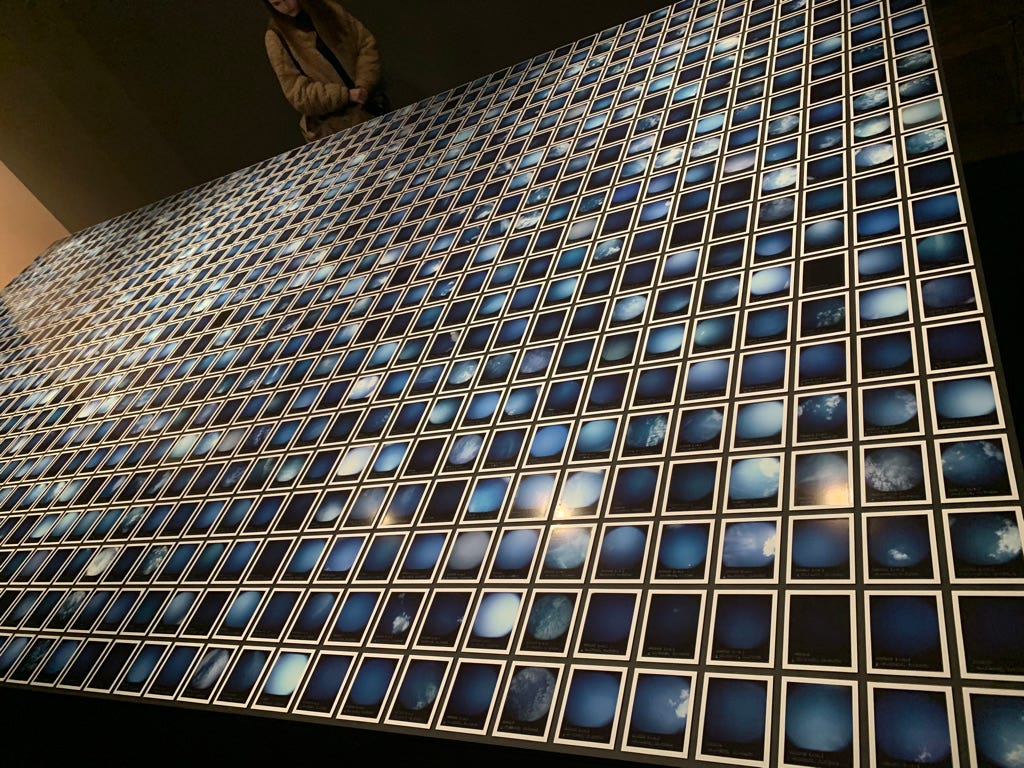

Across the gallery space I saw a platform, its surface displaying the rich blue hues seen in one of my favourite art-forms, the cyanotype. As I couldn’t make out what these hundreds of small, shiny blue squares were supposed to be, I read the label. One Thousand and Seventy-eight Blue Skies (2018) by Anton Kusters. As I read on, my mouth went dry.

“Prompted by the story of his grandfather who narrowly escaped deportation in 1943, Kusters spent 6 years researching and photographing a blue sky at the last known location of every former nazi Germany concentration camp and killing center across Europe.”

Reuben Samama

Each Polaroid image in One Thousand and Seventy-eight Blue Skies is stamped with the GPS coordinates of a Nazi forced labour camp, and the number of people murdered at said camp. Some of these numbers are exact, some are estimated, all are horrific. I suspect that like many people, I associate blue skies with sunshine, and good times, yet here in front of me was a piece of work declaring quite the opposite. Murder, medical experimentation, starvation, rape, torture and abuse all took place under those glorious blue skies, perpetrated by the worst people on the planet. The companion piece, The Tracking of One Thousand and Seventy-eight Blue Skies (2018), by Reuben Samama, is an audio work consisting of a single tone to represent each person murdered by the Nazis. The length of the tone piece is 4432 days, or 12 years. I imagined bodies piling up for 12 years and it made me nauseous.

The themes of memory, the passage of time, and loss are clear in One Thousand and Seventy-eight Blue Skies. Kusters’ use of peel-apart Polaroid film, which can be tricky to apply precisely on some surfaces, is known to fade after several years of exposure to light. The fading and disappearing of the images serves as a allegory for the ever-dwindling number of Holocaust survivors. The sky, common to use all, serves to reminds us of our humanity, and connects us beyond physical borders and specific locations.

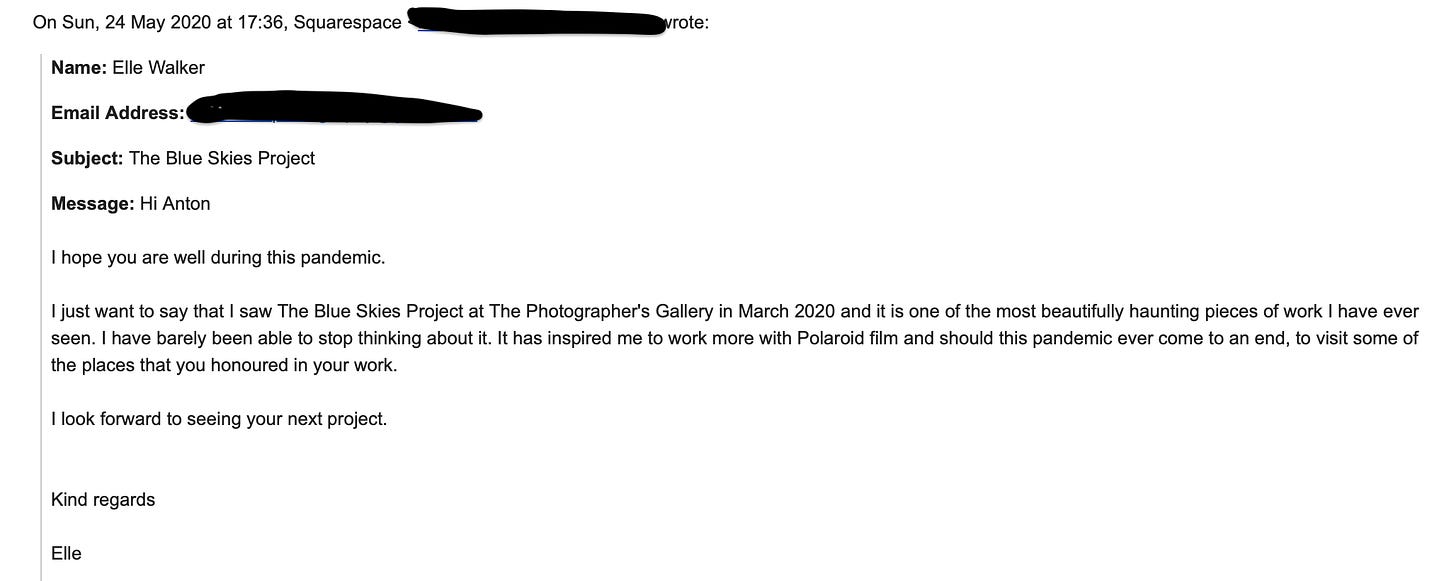

In his book Camera Lucida, philosopher Roland Barthes posits the idea that a dynamic photograph has two main elements: studium and punctum. Studium is the subject matter: it’s obvious, and immediate and understood by everyone. Punctum is the deeper meaning that touches your soul, brings a tear to your eye, or leaves you with a dry mouth and a churning stomach and is different for each individual. Punctum in … Blue Skies, for me at least, is about absence. I don't need to see the atrocities, as it is well known what occurred in those awful places. I’m not exaggerating when I say that whenever I see bright blue sky with big fluffy white clouds, I don’t immediately think of joy. I now think that someone, somewhere is experiencing something quite terrible. I don’t mean to be morose, but isn’t this exactly what great art is supposed to do? Sit somewhere in your subconscious until your conscious mind calls it forth, bringing with it a mix of emotions? After thinking about the piece daily for over two months, I was compelled to reach out to Kusters to tell him how much his work had moved me.1 He was kind enough to respond to thank me. Since 5 March 2020 (1584 days by the time this article is delivered to you), barely a week has passed when I haven’t thought of … Blue Skies. I can only dream of creating work as powerful as this.

One Thousand and Seventy Eight Blue Skies is now part of the permanent collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum. If you’re ever in the vicinity, I urge you to see it.

Which piece of art moves you? Let me know in the comments.

Further reading

https://antonkusters.com/The-Blue-Skies-Project

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/search/?page=1&page_size=15&q=Anton+kusters

https://www.deutscheboersephotographyfoundation.org/en/support/photography-prize.php

Thanks for reading

Quick note: if you don’t already, reach out to your favourite living artists and tell them what their work means to you. They will appreciate it, even if you don’t receive a reply. Artists are needy beings and will love the validation.

I remember this day and art piece well! It made such a lasting impression from the visual impact in the gallery to the meaning behind the work.

Nice to see you used Barthes theory, I miss teaching photography at this level of understanding

Very powerful piece of writing, Elle, about some very powerful photos. Marc Wilson’s ‘A Wounded Landscape’ had a similar impact on me.

https://www.marcwilson.co.uk/project/a-wounded-landscape